Lazzaretto Nuovo isn’t one of those Venetian islands you spot from the vaporetto and decide to hop off spontaneously. In fact, you can’t visit it at all without an appointment. But that’s precisely what makes it so intriguing.

Set in the northern lagoon near Sant’Erasmo and surrounded by peaceful marshes, this 9-hectare island holds an extraordinary story. Long before modern medicine, Venice used Lazzaretto Nuovo as a strategic outpost to prevent the spread of the plague. What remains today is a mix of fortified walls, wild greenery, and traces of daily life from a time when isolation meant survival. It’s a place where you walk and listen, trying to imagine what once happened behind those stone walls.

Quarantine before science

When the plague first arrived in Venice in 1347, they had no real understanding of how it spread. They only knew that it was terrifyingly contagious. Outbreaks could kill up to half the city’s population, and they returned roughly every ten years. People soon realised it wasn’t just direct contact that was dangerous, but also clothing, bedding, and other objects touched by the sick.

In 1423, the Venetian Republic – whose structure you can learn more about in ‘A short introduction to the complicated history of Venice’ – decided to isolate the sick people on a separate island, Lazzaretto Vecchio, to avoid contamination. It was a bold and, for its time, innovative move and the world’s first official quarantine station.

But since Venice was a major port and new plagues often arrived by ship, the government needed a second layer of defence. That came in 1468, when the Senate repurposed Lazzaretto Nuovo for those who might have been in contact with the disease but weren’t showing symptoms yet. The strategic location of the island at the entrance of the lagoon made it possible to stop all ships for inspection.

The island had previously belonged to the Benedictine monks from San Giorgio Maggiore, who used it as a vineyard. The Venetian Republic leased the land and transformed it within the existing walled enclosure: new buildings went up, separated into compartments for people and cargo, all enclosed by high windowless walls. The idea of incubation didn’t exist yet as they had no clue how the disease developed or how long it took to show symptoms. So they chose to isolate people and goods for approx. forty days, just to be safe. That’s where the word quarantine comes from: ‘quarantina’ in Italian, which means ‘approx. 40’.

Everyone on board was confined, and they weren’t allowed to mingle with the others. There were around 100 rooms and 200 beds, but it’s likely the island held up to 500 people at once. Poorer travellers often slept on the ground. Food was provided, but wealthier guests could order fresh produce from a vendor who approached the island by boat. Goods were passed using long sticks to avoid contact, and coins were disinfected with vinegar.

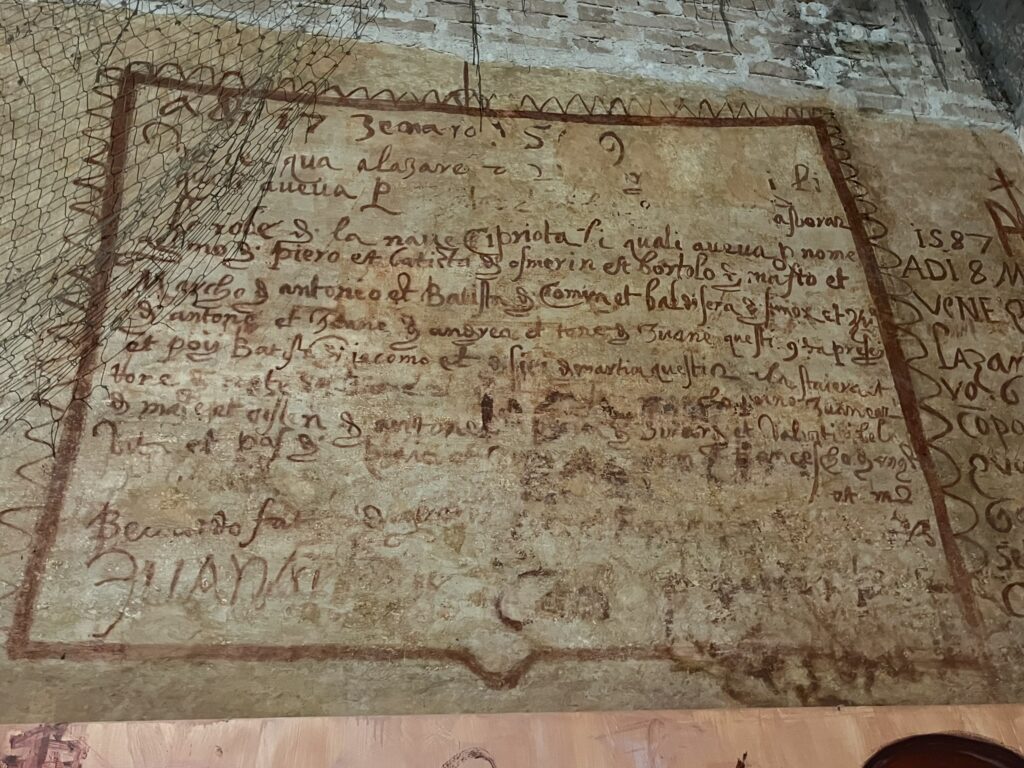

The goods were sanitized in a vast warehouse, the Tezon Grande, which dates back to 1568. Its high ceilings and thick walls still echo the memory of those who passed through. If you look closely, you’ll see old drawings and messages left by workers on its walls in the 16th century. The long arches, now sealed off, were originally open to allow in air and movement, similar to the Gaggiandre in the Arsenale, as described in ‘The fascinating history behind the Arsenale walls’. Today they’re bricked up, but you can still imagine how the space once bustled with activity, and how important this place was in Venice’s effort to contain disease.

Even without scientific tools or lab tests, the Republic of Venice was ahead of its time by systematically isolating both people and goods, and by managing the flow of ships into the lagoon. Venice hasn’t experienced a major outbreak of plague since the 1630s, largely thanks to the strict procedures at the lazzaretti.

If you would like to explore more about how the plague shaped the city, you can also visit the Redentore (featured in ‘The secret garden behind the Redentore church in Venice’) and Salute churches. Both were built as acts of devotion to thank God for deliverance from the plague.

From quarantine to military base and ecomuseum

By the end of the 18th century, the plague had largely disappeared, and the island was no longer needed for quarantine. The Republic handed it back to the monks. But when Napoleon arrived in 1797, Lazzaretto Nuovo took on a new role. It became part of Venice’s military defence system and was used for storing ammunition. The internal walls were demolished, floors were raised, and stone ramparts and earthworks were added. The area with the mulberry trees still shows traces of the tracks once used to move ammunition, and floors were raised to keep powder dry in the damp lagoon environment.

The island stayed in military hands through Austrian and Italian rule, until the army finally left in 1975. By then, nature had taken over, buildings were collapsing, paths were overgrown, and most of its history was forgotten.

Thankfully, a group of dedicated volunteers stepped in. They cleared the island, restored what they could, and began documenting what was left. Today, the Tezon Grande serves as a depot for archaeological finds from the lagoon, and the island even hosts summer workshops for archaeology students. There’s also one of Italy’s first plant-based water purification systems here.

Today, the island is also an ecomuseum dedicated to the local territory and its communities, active in the Venetian lagoon in terms of research projects, exhibitions, and publications. The project develops and supports numerous interventions and organisations in the local area, targeting the tutelage, study and sharing of its historical, environmental and anthropological heritage (archeology, architecture, restoration, nature, artisanal and seafaring traditions, urban studies, agriculture, publishing).

How to visit Lazzaretto Nuovo

The island can only be visited by joining a guided tour. The organisation Lazzaretti Veneziani offers tours every Saturday morning (from March to November), in English. The visit lasts about two hours and costs €10. You can also book a private visit (minimum contribution €150).

The tour starts with a peaceful walk around the island along the ‘Path of the Barene’, about a kilometre long, which circles the island just outside the walls. You will enjoy stunning views over the marshes, the canals, and the lagoon. After the walk, the guide takes you into the island’s core, explaining its layers of history and showing the Tezon Grande, which today doubles as a simple museum. Aside from the Tezon Grande and the old entrance gate, most of the original structures are gone, but the stories and the atmosphere remain strong.

To get there, take vaporetto 13 from Fondamente Nove. The stop is on request, and the island is locked behind a gate, so be sure to book in advance. You can find more info on their website and social media channels. If you’d like a sneak preview, here’s a short clip that shows you what it’s all about.

At the moment, Lazzaretto Vecchio (the other quarantine island) is closed for restoration, but it’s worth keeping an eye on the Lazzaretti Veneziani page for updates. Hopefully it won’t be long before both islands are open to visitors.

Planning to go? Combine your visit with a walk around nearby Sant’ Erasmo (which you can explore in ‘A walk from Sant’ Erasmo to San Giorgio Maggiore with Eva’), or Giudecca, home to the Redentore church (featured in ‘Giudecca: A peaceful island with 10 remarkable buildings’), which was built as a thank-you to God for ending the plague. Whatever you choose, Lazzaretto Nuovo is a quiet yet powerful reminder that long before vaccines and laboratories, Venice had already found its own way to fight the invisible enemy.

Have fun!